NORMANDY

THE HEDGEROWS

“I was over to see Martin and Ronny yesterday and they are both fine, but like myself, have had a few close calls, but I believe if it’s not your turn to get hit, all the shells in Germany can’t hurt you no matter how close they come to you.”

We were alerted on June 5 that we would be crossing the channel on the sixth. We spent the day cleaning our guns and equipment and writing letters. On the sixth very early in the morning, hundreds of planes were in the air headed across the channel toward Normandy. We loaded on British ships and were fed a breakfast of liver that had a green, slimy gravy on it. Needless to say, a lot of us had nothing but coffee. – Sergeant Charles Willsher

It wouldn't be until the night of June 9th that Lawrence and his battalion boarded the S.S Empire Battleaxe and sailed in the darkness towards the beaches of France. They arrived at dawn on the 10th, but the logistics of unloading an entire division took days to complete. The 60th spent that Saturday anxious waiting on the boat surrounded by the explosions of ship guns blasting away at the German strongholds miles inland. On June 11th at 0830, he climbed down the net ladder into a Higgins landing boat and soon was making his way up Utah Beach. The 39th Infantry Regiment was detached and joined the 4th Infantry Division to help clear the strong fortifications north of the beach and attack the town of Quinéville. The 60th and 47th Regiments moved west as planned to assemble in the small towns south and then west of Ste. Mère Église. The problem was the 90th Infantry Division had been unable to push the Germans back to those planned staging areas. It was then decided by General Collins to use the 9th immediately and have them fight through the 90th Division’s lines and reach the objective. The overall goal for the 9th was to slice quickly west through the Cotentin Peninsula to take the town of Barneville on the western coast. Meanwhile the 90th Division would protect their northern flank and the 82nd Airborne would protect their southern flank. This would effectively cut-off all the German forces north of that flank and allow the Allies to squeeze them into Cherbourg and capture its deep harbor docks. With the use of Cherbourg as a major shipping port, the Allies could get equipment and reinforcements from England to the front lines much faster than through the beaches.

Above: The 9th Infantry making their way up Utah Beach past the anti-tank walls. Below left: More troops unload from the landing crafts onto Utah Beach. Below Right: Men of the 9th Infantry Division march off the beach towards the front lines near Ste. Marie-du-Mont.

F COMPANY LOSES ITS CAPTAIN

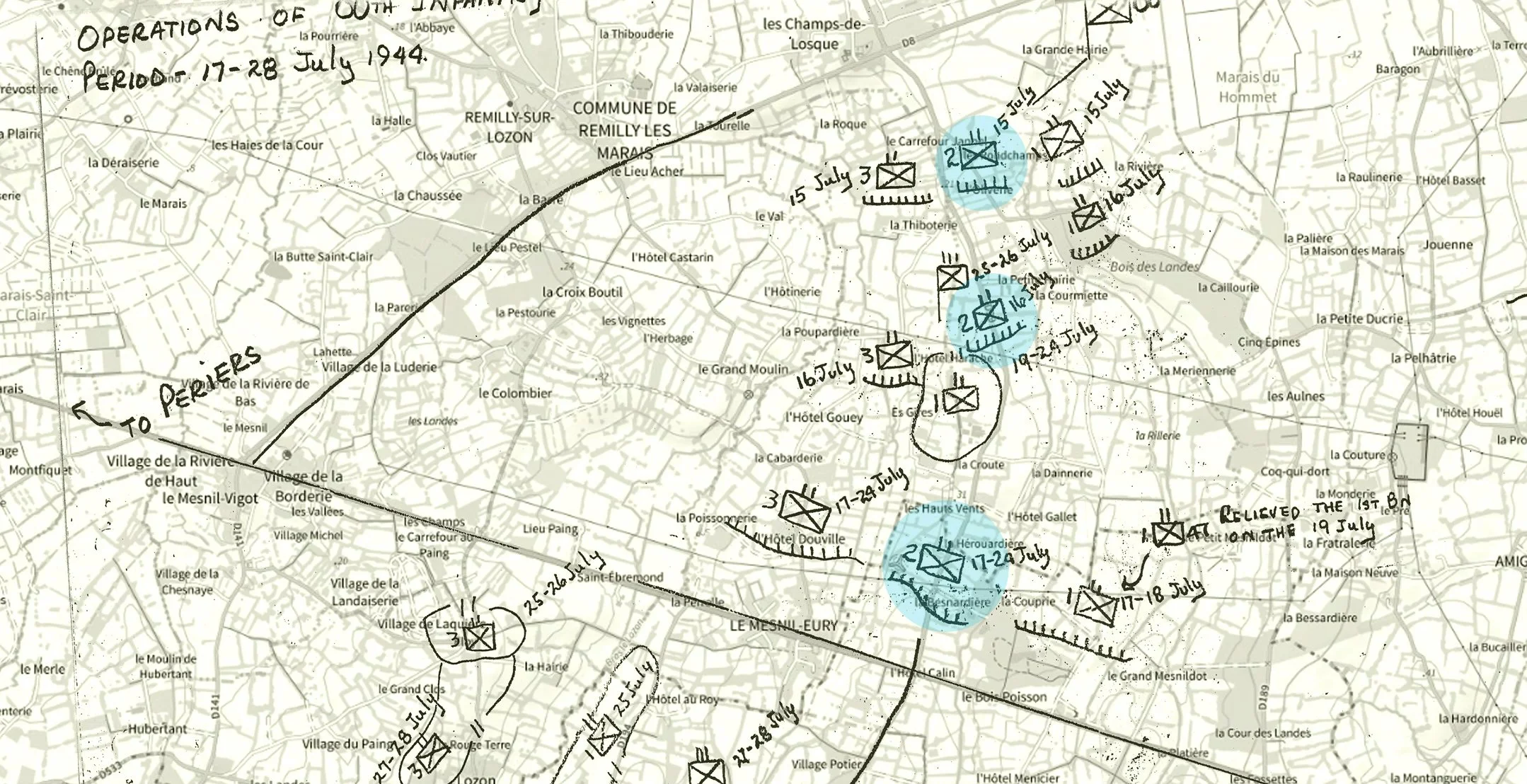

The first days of battle for the 60th in Normandy are highlighted in light blue. The ‘3 Bridges’ is where the Douve River crosses the main road towards Barneville, making that position imperative to getting tanks and trucks across.

The 9th’s first challenge to cut off the peninsula was securing all the bridges over the Douve river that snaked north and south between Utah Beach and Barneville. The 60th went into battle the morning of June 14th, leading the long columns of the 9th Infantry until they could breakout past the regiments of the 90th. The goal was to secure all the small towns on the way to the Douve river, then capture all the bridges intact before the Germans retreated and blew them up. Speed was the key, and the stubborn Germans had become experts in slowing down advancing units in the hedgerows. By noon, with the 3rd battalion leading the way through the maze of orchards and farms, they encountered stiffer resistance approaching Renouf. It was necessary to saturate the town with artillery fire before the infantry could advance. The Germans moved out and the 3rd Battalion entered the town that evening. Lawrence’s 2nd Battalion was then brought up to leap-frog the 3rd on its right flank and together they moved to the main road by dark and dug in for the night.

It had been the first action the men of the 9th Infantry had seen in ten months when their trek across the mountains in Sicily came to an end. In Normandy, they quickly realized all their talent as a mountainous strike force was nullified by the claustrophobic checkerboard of the Normandy hedgerows. It was a problem for the entire invasion force. Allied leaders had not anticipated how the terrain would stall movement and underestimated the German’s cunning strategy of turning each of the thousands of squared-off orchards into perfect killing zones. The hedgerows had been in place since the days of the Romans 700 years earlier. Each and every plot of land, usually rectangles of a hundred or two hundred meters long, was completely enclosed by thick mounds of earth, on top of which would sit hedges five-feet-high on average. Trees, thick brush, knotted roots, vines, barbed wire, and briar all tangled itself into the earthen walls. They acted as natural fences for corralling livestock, prevented flooding from the rivers and marked the boundaries between land owners. The Allies were anticipating the hedgerows they had seen in England, much shorter and less dense. General Collins told General Bradley the bocage was as a bad as anything he had seen in the jungles of Guadalcanal.

The Germans had dug in line-after-line of hidden machine guns. Snipers hid up in the trees and camouflaged tanks became invisible to air power. The German’s had also learned many tricks from fighting the Soviets on the eastern front, they booby-trapped bomb craters and abandoned foxholes with mines to explode when a GI jumped into one for cover. They strung tight wires across the roads at neck height to decapitate anyone sitting in a jeep. Their most effective trick was to shoot at a platoon in the open field as if a sniper was in the trees, causing the men to lay flat on the ground, then pummel them with artillery fire or machine guns. It was quickly trained into every man that best way to stay alive was to move forward and charge the far hedgerow, shooting as you advanced without seeing a target. If you laid down or retreated, you were more likely to die. Rifle squads soon adapted new techniques of moving in small groups up the flanking hedgerows while cover fire came from behind. Tanks were fitted with bulldozer claws to cut directly through the thick walls, with infantry emerging from the gap to attack. Battles were now small, tight skirmishes in thousands of connected football fields.

The war in Normandy would become weeks and weeks of deadly hide-and-seek. In fact, U.S casualties in June and July of 1944 were unexpectedly high, with 7,200 killed and 30,000 wounded. In those two months, the Americans would only travel 50 kilometers, meaning one U.S soldier died for every meter they gained. Each rifle company on average suffered casualties of 60 percent of enlisted men and 68 percent of officers. A U.S Army study of the hedgerow fighting concluded that “The real heroes of this fighting were the soldiers, the platoon leaders, and the company commanders. They met the enemy, they made the decisions which won and lost the host of little battles.”

Above: American riflemen moving through the hedgerows in Normandy. Below Left: A German machine gun nest buried in the hedgerows. Below Right: German troops rush to battle in Montebourg, just north of Ste. Mère Église.

On the morning of June 15th, F Company took off from its line just north of La Bonneville at 0500 hours. The intel reports said that the Germans were bringing up two full regiments directly in the path of the 9th Infantry. The 90th Infantry Division turned northward towards Orglandes and found itself overwhelmed. They reported that 16 tanks were heading south from Orglandes right at F Company’s position. They initially encountered two of these German tanks as well as heavy machine gun fire from German infantry. F Company’s bazooka gunner attempted to stand up and fire at the tanks, but German guns cut him down with a gut-shot. Captain Matt Urban raced to the wounded man, took his bazooka, and had the ammo-bearer follow him through the hedgerows. Urban was able to zero in on the first tank, fire, and blow the tank up into flames. The two men quickly reloaded and hit the second tank. The men of F Company then sprung from their cover and ran up the incline towards the German positions. But the ground started to rumble again, and a third tank emerged from the trees. Urban had reloaded once again, but the tank was able to fire off a round near his position. He jumped for cover and scrambled to the hedgerow when a second blast from the tank exploded next to him. He was seriously concussed and shrapnel shredded the back of his leg, taking out a chunk of his calf muscle. Despite their captain unable to fight, F Company had the advantage and pushed the enemy back with anti-tank guns.

A medic reached Captain Urban and tied a tourniquet around his leg. He refused to be evacuated to the rear, insisting he continue with his men to the next objective. The 1st Battalion on their right flank had been counterattacked by a German battalion with four tanks. Two company commanders had been lost for them as well. 2nd Battalion needed to counter and regain the position lost. F Company decided to carry their wounded captain on a litter and they pushed field-by-field through the German lines. Finally Major Norm Weinberg came up to the front lines to order his friend Captain Urban back to a field hospital. From there he would be shipped back to a hospital in England and remain until the end of July.

A 9th Infantry bazooka team waits for a clean shot on a German tank.

Looking west from Renouf towards Néhou showing the fields Lawrence fought through in the center of the map. The endless maze of hedgerows made for lethal small arms battles between infantry units, with little high ground to observe the enemy. Many times, you heard the enemy before you ever saw him.

3rd Battalion continued its advanced at 0500 the next day with 2nd Battalion leap frogging them at 1100. It was June 16th and the early morning saw a fierce attack by a tank battalion attached to the 82nd Airborne at St. Sauveur-le Vicomte, pushing the Germans to the western side of Douve River. That advance opened up the field for the 9th to make their own sprint to the river. General Eddy told 2nd Battalion commander Major Kauffman to pushed hard past Reignville to the bridges at Ste. Colombe. Their pace was impressive, General Collins called their rush on Ste. Columbe, “one of the most brilliant actions … in the entire war.” They advanced so quickly that morning, even with encountering sporadic machine gun fire, that the rest of the 9th Division thought they hadn't advanced at all or were lost, since no one on their flanks could locate them. But actually, the battalion had moved so far ahead of anyone else, they were all alone at the river. In the process they had killed numerous Germans and taken another 18 prisoner.

A 1944 recon photo of the bridges between Nehou and Ste. Colombe prior to the June 6 invasion. The rivers were larger at the time of the June 16th battle, due to the German’s strategic flooding of all Normandy rivers as a defensive tactic. The building in the center was a creamery, which helped provide cover to the scattered men of E and F company.

At around 1600 hours, E Company crossed the first bridge over the Ste. Colombe River and the second bridge over the Douve River. F Company followed behind, riding on the tanks of B Company of the 746th Tank Battalion. As they moved to the third bridge over the Boille River, they saw it had been blown. E Company continued moving towards Nehou and elements of F Company followed while the tanks retreated back to Ste. Colombe. It was then, on the main road that artillery started bombarding E and F Company in the open. The fire was coming from their left rear where significant high ground lay a few miles away. The 2nd Battalion had moved so far beyond the front lines, they were being attacked from behind. The artillery was ferocious, one shell killed four sergeants in a platoon. The two companies began to scramble for cover in the open fields. Some ran up to the far western hedgerow towards Néhou, where more artillery and small arms fire began to erupt from the town. The bell tower of the church in Néhou gave perfect sight of the Americans. The commanders attempted to regroup a fighting force, but too many men were calling for medics and starting moving back towards Ste. Columbe. Others dug in along the Douve River. For three hours, the two sides fired at each other. American tanks and mortars from Ste. Colombe attacked the high-ground artillery to the south and volleyed shells into Néhou. The rifleman stuck in no-man’s land attempted to dig in and return their own fire, but ammunition was critically low by evening. Major Kauffman took off towards the east, back to the regimental headquarters and returned with a 2 1/2 ton truck full of ammunition. It was a welcomed sight for the weary men in the forward units. Under the extreme duress, they held their positions as the sun was setting around 11 p.m. (British double-summertime set time two hours ahead, meaning dusk wasn't until late evening). It was at that time 3rd Battalion of the 60th reached them and the two established a firm bridgehead. Soon thereafter 1st Battalion arrived after moving through their own firefights during the day. The courageous defense under the lengthy assault of artillery, mortars, machine-guns, and small arms fire earned the 2nd Battalion its second Presidential Unit Citation.

PRESIDENTIAL UNIT CITATION

The 2nd Battalion, 60th Infantry, is cited for extraordinary gallantry in action on 16 June 44, in the vicinity of Ste. Colombe, France. Early on 16 June, the 2nd Battalion, 60th Infantry, on the left flank of the 9th Infantry Division in the attack, stormed the German defenses, overran their objective in the face of heavy German mortar and machine-gun fire, and proceeded to cut the main highway to the northwest. During this drive the enemy fought desperately to prevent a break-through, but the battalion advanced well out in front of the remainder of the division, thereby losing contact with the units on its right and left. Instead of withdrawing to a safer position, the battalion commander, realizing the urgency of securing a bridgehead west of the Douve River as quickly as possible, continued the advance of his battalion beyond its assigned objective. Gaining a foothold on the western bank of the Douve River by attacking across an exposed causeway and the adjacent marshlands west of Ste. Colombe, the battalion continued to hold this precarious position for 7 hours until reinforced by the fire of tanks from the high ground on the west bank of the river, as the enemy made many fierce but futile attempts to force them back. The daring action of the 2nd Battalion, 60th Infantry, in advancing far beyond its objective and crossing the Douve River in the face of the stiffest enemy resistance was a major factor in the success of the VII Corps in the rapid cutting of the Cherbourg Peninsula and the speedy capture of Cherbourg, and exemplifies the aggressive spirit of every man in this unit.

Above: The third bridge, present day, looking west towards Néhou. Note the original stone walls still remain on the river banks, but modern fences show where the bridge was blown. In the distance you can see the bell tower of the church in Néhou where the Germans sighted their fire on E and F Company stranded along the road and in the fields ahead. Below: 9th Infantry soldiers anticipating the enemy in the fields around St. Sauveur Le Vicomte.

The following morning the 60th occupied Néhou, finding the Germans had abandoned it. The front lines of the 9th and the 82nd now worked in unison and easily pushed on to the high ground surrounding Barneville with fighter-plane cover assisting them in the early hours. The 1st Battalion took hill 133 while the 2nd took hill 145. By nightfall, General Eddy passed the 60th on the road yelling, “We’re going all the way tonight!” The Contentin Peninsula had been effectively sealed off hours later. By dawn, tanks arrived to the deserted coastal town. The next days saw many disorganized German units trying to push through the American lines and avoid being trapped, but their efforts failed due to the strong northern flank set up throughout the main advance. News of the the victory spread quickly in the papers, championing the decisive assault as one of the greatest victories of the war.

Omar Bradley has done it again. Slipping stronger units past the lines of their tiring comrades, he once more smashed unexpectedly through the Germans to cut off Cherbourg, just as he broke through to doom Bizerte, a little over a year ago. And he used the same outfit – the battle-tested Ninth Division – to strike the decisive blow… The blow that broke the Nazi’s back below Cherbourg was clever one and aroused real enthusiasm. – Capt. Lowell Limpus, New York NEWS

The hedgerow-to-hedgerow fighting of the 9th Division across the Cherbourg Peninsula from sea to sea must rate as one of the most brilliant military successes of United States history. For four days I accompanied these veterans, who, not only had turned the tide in Tunisia with the capture of Bizerte, but also helped wind up the Sicilian campaign with the seizure of Randazzo. They were brought to France to chop the tip off the strategic peninsula and isolate the Germans in Cherbourg… The renowned heroes of Port Lyautey and Bizerte, pushed along the flank to Barneville, encountered severe resistance at the little town of St. Jacques de Nehou. They bore the brunt of an enemy counter-attack which was dispersed by the artillery ‘serenade’… Accomplishments to date have put the 9th Division in the forefront of United States forces in the European and African theaters. – Thomas R. Henry, Washington D.C STAR

Above: Map of the western coast of the Cotentin Peninsula showing the 2nd Battalion’s drive to Hill 145 and their attack on the German’s attempt to breakout from Bricquebec. Below left: Map of the open hills surrounding Cherbourg. The blue circle highlights the 2nd Battalion’s area of battle and the stubborn high ground northwest of Flottemanville-Hague. Below right: Members of the French Underground meet with a captain and lieutenant of the 9th Infantry outside of Cherbourg. The information the Underground provided to troops in France was instrumental to their success, sometimes shortening a battle by days and saving an untold amount of American lives. The Underground operated in small cells of 5 men, non of which knew the identity of anyone in the other cells. When liberated, they came out wearing armbands to identify their allegiance, sometimes surprised to see their own neighbors were also in the Underground.

ON TO CHERBOURG

The news of the peninsula being sealed off elated the entire Allied war machine and the press, however the 9th still had to clear out hedgerow after hedgerow of fanatical German fighters, with each field and orchard presenting another chance to be killed. The men hadn't had an opportunity to shower or eat a hot meal or even change their uniforms, now tattered and soaked in sweat and blood. They moved up the peninsula on the left flank. The 4th and 79th Divisions moved up abreast of them encountering the stiffest resistance due to the Germans retreating to better fortifications in the Fortress Cherbourg area. The 60th Regiment made excellent progress, but found themselves in a difficult section of wide-open rolling hills dotted with pockets of German resistance holding the high ground. The Americans employed their dominance of the skies above Normandy at this point, but that presented a serious problem of its own. Marking the targets for dive bombers and fighter planes relied on colored smoke. On June 22nd, during a massive bombardment, the smoke drifted in the strong coastal winds towards the lines of the 60th and 47th Infantry. The bomber dropped payloads on their own men and planes strafed them with machine gun fire. It was a common occurrence to see men die from accidents and friendly-fire, and for the 9th Infantry Division, it would foreshadow a much larger event to come nearly one month later to the day. Regardless of the American casualties by friendly fire, the air bombardments prior to infantry assaults proved to be a devastating one-two punch for the Germans. Although some hills proved to be more challenging than anticipated.

In particular, the hill west of the town of Flottemanville-Hague, four miles to the southwest of Cherbourg, featured a German defense of pillboxes, anti-tank guns, machine guns, artillery, and mortars. It was here that the 60th would see its second posthumous Medal of Honor awarded. He was a platoon leader in E Company named John E. Butts. He was wounded once in the June 14th fighting near Orglandes and once again while holding the bridgehead at the Douve River. His leadership during the fight at the river was instrumental in keeping the battalion intact and functioning. It had been a week later and still he had continued to lead his platoon up to Cherbourg while recovering from his wounds, refusing all aid. It was at the base of a rolling hilltop that his platoon struggled to advance and he was hit with multiple bullets in the stomach by a machine-gun. He continued to lead, sending his squad on a flanking maneuver. While he held his stomach together with one hand, dying, he stumbled up the hill directly in front of German defenses to distract them from seeing his men flanking the position. The Germans cut him down, but the ploy worked and his squad ambushed the pillboxes to take the hilltop.

2nd Lieutenant John E. Butts

MEDAL OF HONOR RECIPIENT

The President of the United States of America takes pride in presenting the Medal of Honor (Posthumously) to Lieutenant John E. Butts, United States Army, for conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at risk of life, above and beyond the call of duty while serving with 60th Infantry Regiment, 9th Infantry Division. Lieutenant Butts heroically led his platoon against an enemy in Normandy, France, on 14, 16, and 23 June 1944. Although painfully wounded on the 14th near Orglandes and again on the 16th while spearheading an attack to establish a bridgehead across the Douve River, he refused medical aid and remained with his platoon. A week later, near Flottemanville Hague, he led an assault on a tactically important and stubbornly defended hill studded with tanks, antitank guns, pillboxes, and machine-gun emplacements and protected by concentrated artillery and mortar fire. As the attack was launched, 2d Lt. Butts, at the head of his platoon, was critically wounded by German machine-gun fire. Although weakened by his injuries, he rallied his men and directed one squad to make a flanking movement while he alone made a frontal assault to draw the hostile fire upon himself. Once more he was struck, but by grim determination and sheer courage continued to crawl ahead. When within 10 yards of his objective, he was killed by direct fire. By his superb courage, unflinching valor, and inspiring actions, 2d Lt. Butts enabled his platoon to take a formidable strongpoint and contributed greatly to the success of his battalion's mission.

With the whole of three divisions tightening in on Cherbourg, warnings were sent to Major General Karl-Wilhelm von Schlieben to surrender his forces on June 22nd. He offered no reply. By the 24th, the 60th was held back to defend the northwest flank of the invading battalions and gun down any enemy convoys that might slip through the front lines. On the 25th, the 47th Regiment of the 9th entered the city in the west, earning its 2nd and 3rd Battalions a Presidential Unit Citation of their own for fighting off a savage resistance by the German arsenal garrison. They captured 2,600 prisoners, 25 anti-aircraft guns, hundreds of small arms, and liberated the Navel Hospital of Cherbourg – freeing over 150 wounded Americans. By the end of the day, the 47th suffered 113 casualties. The following day, small fighting continued in the city with zealous snipers and rooftop machine gunners. But the Americans had them cornered and soon hundreds more Germans came out waving white flags, including von Schlieben and Admiral Walter Hennecke, who had succeeded in destroying the Cherbourg Harbor, delaying the full use of it to the Americans by weeks.

Above (L to R): A company invading Cherbourg advance through a field of dead Germans and cows on the 27th. Troops encounter General von Schlieben and Admiral Walter Hennecke as they surrender. 9th Infantry General Manton Eddy communicating with his officers outside of Cherbourg. Eddy traveling in a jeep with von Schlieben after his surrender. Troops lead lines of surrendering Germans from the city. A captain stands near the body of a German defender in the city.

CLEARING THE HAGUE PENINSULA

After clearing out the enemy from Cherbourg, the 79th and the 4th Infantry Divisions turned south to join the front lines pushing their way in bitter fighting towards St. Lo. In the wake of the invasion, German reinforcements and counter-attacks were fully committed to keeping the Allies in Northern France. The 9th was left all alone to clear out all resistance on the Hague Peninsula west of Cherbourg. With leap-frogging infantry advances, artillery and air support – the objectives would be relatively easy, but nonetheless a fanatical enemy with nothing to lose was waiting for them. The last three days in June saw the beginnings of terrible weather that would continue for next month at least. The invasion beaches had been thrashed by storms, hurting the supply routes and reinforcements. The enemy strength was estimated around 3,000 – the remains of the 709th and the 243rd Divisions. However the 9th soon realized those numbers were only about half the actual resistance. The main objectives in the German line, which was to be assaulted on 30 June, were Beaumont-Hague, Greville, and Gruchy. Civilians reported that Greville was the strongest point in the peninsula. The entire ridge from Greville north was heavily fortified with concrete shelters built into the slopes, as well as turreted machine guns, mortars, and antitank guns. The forward approaches were defended by firing trenches and antitank ditches. Entrenchments of the secondary line were located several hundred yards back. The area was no longer the confined maze of hedgerows like the bocage region. This terrain, particularly the commanding ground to the west, was barren and desolate, with almost unobstructed fields of fire.

On the morning of the 30th, Lawrence and F Company approached north towards Greville, Germans were encountered in the trenches and a close-in, grenade-throwing fight developed. The town, supposedly the strongest point in the German line, was entered by 0900. The enemy had been overwhelmed by superior American fire power. The capture of Greville occurred so much more rapidly that expected that planned artillery concentrations had to be canceled.

The 3d Battalion attacked toward Gruchy but was stopped short of the village by heavy mortar fire. The 2nd Battalion was asked for assistance and it adjusted mortar and artillery on the Gruchy position. Meanwhile, the 2nd Battalion continued to advance to a road junction west of Greville, where it was ordered to hold until the 3rd could draw abreast. It continued to get 20-mm and mortar fire from positions to the northeast and southwest and the 1st Battalion was committed on the left to relieve some of the pressure. Advancing slowly in the face of mortar fire, the 3rd Battalion reached Gruchy by noon but was still under fire from the main German positions on the ridge to the west and south. In the early afternoon a 2nd Battalion concentration of artillery fire began to flush prisoners from the ridge, and both Gruchy and the main German positions were cleared by 1700, the 3rd Battalion moving on to a hill 900 yards west of Gruchy. By this time the 1st and 2nd Battalions, moving against diminishing resistance, were almost at Digulleville, three miles farther west.

The German line in the 60th Infantry's zone was also completely broken during the day through action of the 2nd Battalion. The 1st Battalion continued to be held in the vicinity of Road Junction 167 and did not reach its line of departure. The 3rd Battalion was halted after an advance of about 300 yards, but the 2nd Battalion had moved up during the night to a position north of the highway junction, and it was ready for the advance. Its attack was to be led by Company E, which was to move south of the road, while the rest of the battalion was to advance directly up the road. The men had had only two hours' sleep and Company E had no officers except Captain Sprindus, commanding, and Lt. John I. Cookson, the executive officer. The attack was delayed as it became necessary to fill in an antitank ditch, and the 2d Battalion did not jump off until an hour after the other battalion.

Company E crossed the road despite machine gun fire and slipped through a mine field south of the highway. They advanced up the hill in a dramatic charge with squads in skirmisher formations, firing as they went. It had no supporting fire except for a short volley of 60-mm mortars and the smoke laid down at 0800, the time originally set for the attack, had long since faded. Captain Sprindus was up-front in the middle of the mine field, removing each one he saw to clear a narrow path for the men as they surged forward in their bold assault.

As the 1st and 2nd Platoon moved across the first hill, 3rd Platoon went into a draw to the south, swung west, and then advanced north on the town of Beaumont-Hague along the river bed east of the Vauville road. Company F, meanwhile, was driving up the right side of the main highway, with tanks of Company C, 746th Tank Battalion, moving ahead several times to fire into hedges and at other targets. The tanks apparently demoralized the Germans and Major Kauffman ordered Company F to get on the road with the tanks and proceed directly into the town and aid Company E. Before noon the town was cleared and 150 Germans were taken prisoner. Continuing the push, Company F started out for Jobourg.

The enemy's organized defensive line in the peninsula had been thoroughly shattered by the attacks on the Beaumont-Hague and Greville positions. Although other fortified points lay farther west, the enemy never again offered anything more than delaying opposition, and the drive up the peninsula became, for the most part, a mop-up operation. The 9th Infantry’s objective of taking the Cotentin Peninsula was finally over. It had been an arduous month for the men. From D-Day to July 1st, the 9th had captured 18,490 prisoners. Their own losses had been significant: 390 killed and 1,851 wounded. An editorial in the Boston GLOBE would say:

“If any unit has earned the right to be called Hitler’s nemesis, it is the U.S. Ninth Division. Here is a group that really thrives on tough opposition. It cracked the enemy at Bizerte in that memorable North African campaign and now has led the amazing surge across Cherbourg peninsula, which has overshadowed every other invasion accomplishment.”

Ernie Pyle was embedded with the 9th all through their advance in the month of June, in his book Brave Men, he details his observations of the men once they had taken Cherbourg:

The soldiers around us had a two weeks’ growth of beard. Their uniforms were worn slick and very dirty—the uncomfortable gas-impregnated clothes they had come ashore in. The boys were tired. They had been fighting and moving constantly forward on foot for nearly three weeks without rest—sleeping out on the ground, wet most of the time, always tense, eating cold rations, seeing their friends die. One of them came up to me and said, almost belligerently, “Why don’t you tell the folks back home what this is like? All they hear about is victories and a lot of glory stuff. They don’t know that for every hundred yards we advance somebody gets killed. Why don’t you tell them how tough this life is?” I told him that was what I tried to do all the time. This fellow was pretty fed up with it all. He said he didn’t see why his outfit wasn’t sent home; they had done all the fighting. That wasn’t true at all, for there were other divisions that had fought more and taken heavier casualties. Exhaustion will make a man feel like that. A few days’ rest usually has him smiling again.

The division moved south to Les Pieux on the western coast, just north of their June 17th objective at Barneville. There they could finally change clothes, shower, shave, and write home. Movies were shown and for one day a stage was setup for a performance of French song and dance girls and comedians. For at least one week they could rest in relative safety and celebrate the Fourth of July.

Above left: A Ninth Air Force bomber over the Hague Peninsula after dropping over the coastal battery at Auderville in the distance. Above right: Railway guns near Laye on the peninsula that fired constantly at the 9th Infantry until they took the position on June 30.

July 3, 1944

Dear Mother,

Well this is the first time I had to write since I left England. I’m fine and I’ve been lucky so far. I’ve been here since the beginning and it’s been pretty rough. The weather has been bad and we only had a few sunny days since we were here. They used to tell about the mud in the last war, well I got my feet in it now. The people seem glad to see us, that is, most of them. Ronny was alright when I saw him three days ago, and I suppose he will write when he can. I haven’t seen Martin since the first day, so I don’t know about him. Sorry to hear about Gerald, but he sure had a tough time. Will write more when I can.

Lots of love to all,

Lawrence

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

July, 6 1944

Dear Mother,

I had a few minutes today so will write a few lines. At the moment everything is quiet where I am and it sure is nice to have it that way once in a while. I’ve been taking a few days break to rest up a bit. I was over to see Martin and Ronny yesterday and they are both fine, but like myself, have had a few close calls, but I believe if it’s not your turn to get hit, all the shells in Germany can’t hurt you no matter how close they come to you. It has been very damp and rainy weather up until the last few days, so you can imagine how it was in those water-soaked holes at night without much to keep you dry. It’s funny though, the boys don’t complain much about it and are always joking about something or other. If it wasn’t for the companionship and buddy system, I’d have gone nuts long ago. We got a new chaplain or priest just before we left England and he has stayed right up there with us all the time and has brought us communion practically to our foxholes. Everyone knows him as Father Joe. He’s only been with us a month or so, but everyone seems to know him. The people are real friendly where I am now and we get fresh butter and milk from them. It sure goes good with our rations. At first they didn’t seem to know what to do and were just a little bit scared of us, but that soon wore off. Well, I’ll close for this time and write soon again. Don’t worry, I’m doing alright. Until next time.

Lots of love to all,

Lawrence

“Father Joe”

Father Joe was likely Capt. (Chaplain) Joseph C. Sharp. Prior to joining the 60th in England, he was the regimental chaplain for the 47th Infantry Regiment during the campaigns in North Africa and Sicily. In the intense battle at El Guettar, while the 60th was holding the line at Maknassy, Captain Sharp was awarded the Silver Star. Most nights throughout the war it was the gruesome duty of chaplains to go out on the front lines and collect the bodies of fallen GIs. At El Guettar he led a squad of men through a mine field under intermittent flares and enemy observation. They collected five wounded men from “no man’s land”.

July 8, 1944

Dear Mother,

Well everything is O.K with me yet. I got your letter of the 27th yesterday and was glad to hear everyone is well. The package Aunt Lizzy sent came today, so I’ve been eating I as I write. I heard from Gene a couple weeks ago but I haven’t got his letter answered yet. It has cleared up some the last few days so that makes it a lot nicer for us. I’d like to write to Grandpa and Grandma, but I just don’t know what to say. I know how they feel about Gerald’s death and it’s hard to put it in a letter what I’d want to say. Well I must cut this short again, probably will have a chance to write soon again. Write whenever you can.

Love to all,

Lawrence

THE PUSH OUT OF NORMANDY

On July 9th the week of rest was over and the 9th Infantry Division assembled southeast of Carentan to relieve elements of the 30th Division and the 113th Calvary group. It was to be the final push out of the Normandy hedgerows and reach the open terrain of France. With air superiority and Sherman tanks rolling off the assembly lines in incredible numbers, the Allies could then quickly shove the German’s out of France for good.

The fighting during the month of July would be torturous. The rain was relentless and the area of battle was a series of swamps and thick hedgerows with steep-sided galleys. Swarms of mosquitoes, millions in numbers, drove the men crazy at night without any access to netting. The confined fighting, field after field was also maddening. In July, the 9th would average 300 casualties a day.

Ernie Pyle wrote extensively about the fighting in July:

The fields were usually not more than fifty yards across and a couple of hundred yards long. They might have grain in them, or apple trees, but mostly they were just pastures of green grass, full of beautiful cows. The fields were surrounded on all sides by the immense hedgerows. The Germans used these barriers well. They put snipers in the trees. They dug deep trenches behind the hedgerows and covered them with timber, so that it was almost impossible for artillery to get at them. Sometimes they propped up machine guns with strings attached so that they could fire over the hedge without getting out of their holes. They even cut out a section of the hedgerow and hid a big gun or a tank in it, covering it with bush. Also they tunneled under the hedgerows from the back and made the opening on the forward side just large enough to stick a machine gun through. But mostly the hedgerow pattern was this: a heavy machine gun hidden at each end of the field and infantrymen hidden all along the hedgerow with rifles and machine pistols.

It was a slow and cautious business, and there was nothing dashing about it. Our men didn’t go across the open fields in dramatic charges such as you see in the movies. They did at first, but they learned better. They went in tiny groups, a squad or less, moving yards apart and sticking close to the hedgerows on either end of the field. They crept a few yards, squatted, waited, then crept again. If you could have been right up there between the Germans and the Americans you wouldn’t have seen many men at any one time—just a few here and there, always trying to keep hidden. But you would have heard an awful lot of noise. Our men were taught in training not to fire until they saw something to fire at. But the principle didn’t work in that country, because there was very little to see. So the alternative was to keep shooting constantly at the hedgerows. That pinned the Germans to their holes while we sneaked up on them. The attacking squads sneaked up the sides of the hedgerows while the rest of the platoon stayed back in their own hedgerow and kept the forward hedge saturated with bullets. They shot rifle grenades too, and a mortar squad a little farther back kept lobbing mortar shells over onto the Germans. The little advance groups worked their way up to the far ends of the hedgerows at the corners of the field. They first tried to knock out the machine guns at each corner. They did this with hand grenades, rifle grenades and machine guns.

Usually, when the pressure was on, the German defenders of the hedgerow started pulling back. They would take their heavier guns and most of the men back a couple of fields and start digging in for a new line. They left about two machine guns and a few riflemen scattered through the hedge to do a lot of shooting and hold up the Americans as long as they could. Our men would then sneak along the front side of the hedgerow, throwing grenades over onto the other side and spraying the hedges with their guns. The fighting was close—only a few yards apart—but it was seldom actual hand-to-hand stuff. Sometimes the remaining Germans came out of their holes with their hands up. Sometimes they tried to run for it and were mowed down. Sometimes they wouldn’t come out at all, and a hand grenade, thrown into their hole, finished them off. And so another hedgerow was taken and we were ready to start on the one beyond.

In a war like this everything was in such confusion that I never could see how either side ever got anywhere. Sometimes we didn’t know where the enemy was and didn’t know where our own troops were. As somebody said one day, no battalion commander could have given you the exact location of his various units five minutes after they had jumped off. Gradually the front got all mixed up. There were Germans behind us and at the side. They would be shooting at us from behind and from our flank. Sometimes a unit got so far out ahead of those on either side that it had to swing around and fight to its rear. Sometimes we fired on our own troops, thinking we were in German territory. It was hard to see anything, or even tell from the sounds, for each side used some of the other’s captured weapons.

Adding to the confusion, the Germans had reduced themselves to covert trickery in the hedgerows. They notoriously wore American uniforms and spoke unaccented English to lure GI patrols into deathtraps. It was an environment foreign to anyone fresh from the boats. Replacement soldiers were everywhere since the skirmished fighting withered company numbers day-by-day. Many replacements simply died of shock without ever receiving a scratch. The good replacements, regardless of rank, learned from the ‘old-guys’. They learned not to fasten their helmet straps, since shell concessions could whip the helmet off in such ferocity it would snap a GI’s neck. They learned how to hear the “pop” of a sniper’s bullet overhead and then locate the source by the “crack” from his rifle seconds later. Men like Lawrence were a valuable commodity in the month of July. There were fewer and fewer riflemen with the extensive experience he had. It was likely that without a rank change from private first class to sergeant or staff sergeant, he was already a squad leader. Many times in the chaos of battle, official promotions were delayed. You simply inherited the job of your dead superior.

The Germans had anticipated a softness in the American lines where the 9th had been assigned to take over. There was already a plan for them to use Germany’s finest armored division, the Panzer Lehr, to strike the 9th’s sector and split the lines at Isigny. On July 11th, the attack came. Brilliantly, the 39th’s defenses around St. Jean-de-Daye absorbed the German attack and allowed the 60th and 47th to counter them on the flank, annihilating the Panzer convoys. Presidential Unit Citations were awarded for the 899th Tank Destroyer Battalion and the 2nd Battalion of the 39th Regiment. The following day the 9th Division resumed its push south and west. The 39th and the 47th advanced towards Le Desert encountering fierce resistance. The 60th had an easier path west, since the Germans had abandoned the Bois du Hommet area and the swamplands surrounding Tribehou. June 12th still was a solemn day for the 60th. The beloved and respected commander of 2nd Battalion, Major Mike Kauffman, was badly wounded in the arm during a counter-attack and sent home. It was the loss of yet another irreplaceable officer for the 9th, replaced by another ‘ninety-day wonder’ – slang term to describe an officer fresh from the states with no combat experience.

The next objective for the 60th was the well defended high ground around Les Champs de Losque which they captured on the 16th, giving them access to the critical road junction. The overall objective of reaching the St. Lo - Périers highway was in sight and nightly patrols crossed it by July 18th. The movement of the 9th Infantry was halted, giving time for all units to come abreast of each other on the line. Generals were preparing for a massive offensive and on July 19th, Field Order #6 was given to the 9th Division – outlining their part in the advance. The end of July had been an eventful few days for the war: The smoldering ruins of St. Lo had been captured, famed German Field Marshall Erwin Rommel was wounded in an air-attack, Harry Truman won the nomination for Vice President, and Hitler narrowly survived an assassination attempt. The end of July also marked the end of the Normandy invasion that took nearly two months to achieve. It was on to the next stage of the war and after several days of false starts due to bad weather, a “Second D-Day” was set for July 24th.

Its codename: Operation Cobra.

Map showing the front lines in late July, just prior to the Operation Cobra ‘Breakout’. The location of Lawrence’s F Company is shown by the black ‘F’. The blue rectangle behind the German line shows the area of the planned bombing.

July 23, 1944

Dear Mother,

Well it’s been about two weeks again since I had a chance to write. I’m well, and still sweating it out. It’s been pretty rough and I do mean rough, but I hope it will be over soon. There’s still plenty of mud, but I’m getting used to it now. I haven’t seen Ronny for a few days now, so I can’t say how he is, I hope O.K. I haven’t had a hot meal for nearly two months, but we do get plenty of rations and get to heat them once in a while. Haven’t got much mail lately, but of course I haven’t done any writing myself. I heard from Gene not long ago and he seems to be getting along fine. Well I’ll write when I can again. I’m in a hole right now and the shells are going over thick.

Love to all,

Lawrence

Two Bronze Stars

Lawrence was awarded two Bronze Stars during his service, signified by a bronze oak leaf cluster pinned on the star’s ribbon. They were awarded at some point in Normandy since he never mention them to his mother in his England letter detailing the medals on his uniform. The citations are unavailable, but the medal pictured here does exist.

OPERATION COBRA: DAY 1

His name on the July 23rd letter showed his new rating, staff sergeant. Normally a battlefield promotion from private first class (E-3) to staff sergeant (E-6) is extremely unlikely, but it showed the depletion of the platoons in the 60th after two months in Normandy. A staff sergeant was either a squad leader or a platoon guide. Each rifle company was composed of three rifle platoons. Each platoon had three squads. In each squad there was: 1 squad leader, 1 assistant squad leader, a 3-man automatic rifle team (BAR team), 2 rifle grenadiers, and 5 rifleman. In a much earlier letter, Lawrence expressed his desire to be nothing but a private, responsible for no one but yourself. It was a wise opinion to have considering how the odds of survival drastically decreased being a squad leader, platoon leader, or company commander. For the first time in his war, he was now officially responsible for 12 men on the front lines; on the eve of one of the biggest offensives in the entire war.

General Omar Bradley simply had enough of the frontal infantry attack strategy. The German resistance was still too strong to achieve any significant success without brutal attrition. The decision was made to carpet bomb the most important section of the front line with an overpowering amount of Air Force bombers. It would be such a massive saturation of bombs, that the front infantry units could rush through immediately afterward and reach the vital road junctions south of the St. Lo - Périers highway. The towns of Marigny and St. Gilles were the objectives assigned to three divisions: the 9th, the 4th, and the 30th. The 83rd and 35th Divisions would create the flanks. With this punch of the German lines, the 1st Infantry, 2nd Armored, and 3rd Armored Divisions could funnel through and race out of the bocage country to open fields. The one uncertainty of the plan, was the extensive use of air power. Over 3,000 planes were to fly within a mile of the American lines and drop a staggering amount of bombs over a small area of 6,000 yards by 2,200 yards. It would be a first in the history of warfare and Omar Bradley declared, “I’ve been wanting to do this now since we landed. When we pull it [off], I want [it] to be the biggest thing in the world.”

The 9th had seen the dress rehearsal for such an attack before the invasion of Cherbourg and had lost numerous soldiers to friendly fire when the location smoke signals drifted over the American lines. In that event, a position of soldiers 2,000 yards behind the marked lines were hit three times, that distance was twice the planned distance for Operation Cobra. In another event, troops had moved back 6,000 yards before a carpet bombing. By the time they covered the distance to reach the line, the German’s had recovered and reinforced their position. There was no easy answer and Bradley decided a troop withdrawal of 1,200 yards would work as long as the bombers came from east-to-west and bombed in a parallel line, instead of flying in from behind the American lines. Smoke signals would still be used, along with florescent panels to mark the troop positions. The tops of all trucks were painted with a large white star as well. The cost of civilian lives would be ignored, there was no way to evacuate the French residents in the bombing area without giving the Germans a warning as well.

A total of 1,586 heavy bombers were dispatched in three waves. The planes approached in a perpendicular direction from behind the lines, not as ordered, but the first two waves all saw heavy cloud cover and most brought back their bombs to the airfields. A few did drop over targets they spotted well south of the primary target area. On the third wave, 317 planes were able to drop over 2,800 bombs. However most fell beyond the target area except for 12 planes that drop their payload of 473 high explosive bombs within the American zone, killing 25 troops from the 30th Division. While the last formation was still over the target, it was decided that the breakout by ground forces would have to be postponed until the next day.

“Owing to a mixup in the orders, the bad weather and human error, many bombs fell behind our own lines, killing 25 and wounding 131. One reason for the error was that the planes flew a course perpendicular to our lines rather than parallel to it as I had been assured they would. I have seldom been so angry. It was duplicity – a shocking breach of good faith... I launched an immediate investigation to find out why the airmen had bombed on a perpendicular course rather than a parallel one as promised. To my astonishment, the Air Force brass simply lied, claiming they had never agreed to bomb parallel to the road. Not only that, they put me over an impossible barrel. They would not mount a second attack except perpendicularly to the road. Fearing the Germans were onto us, I had no choice but to accept what the airmen offered and we reset the jump-off for the following day, July 25.” – General Omar Bradley

Bradley’s anger was soon rebuffed by the Air Corps Generals, who laid out the problems with a parallel bombing. It would drastically increase the time the bombers spent over enemy lines and the chances of being shot down. It would increase the time needed to complete the entire bombing by several hours. It also was much more effective to bomb across the widest axis of the zone, the 6,000 yards of front lines as opposed to the 2,200 yards beyond the highway. They simply couldn’t fit that many bombers in that narrow of space. The ultimatum had been delivered and Bradley faced a tough decision for July 25th: Repeat the perpendicular bombing run risking more American lives, bomb on a far less effective parallel run, or forgo the bombing all together leading to another bloody frontal assault. With the weather reports indicating the 25th would be his only window for a week, he decided to repeat the perpendicular bombings.

OPERATION COBRA: DAY 2

Ernie Pyle chose to join the 4th Infantry Division at the front line for the ‘Breakout’. Many war correspondents were alerted to the operation and scrambled to get their spot for the next big assault of the war. Here’s his story of the second day’s bombing:

If you don’t have July 25 pasted in your hat I would advise you to put it there immediately. At least paste it in your mind. For I have a hunch that July 25 of the year 1944 will be one of the great historic pinnacles of this war. It was the day we began a mighty surge out of our confined Normandy spaces, the day we stopped calling our area the beachhead and knew we were fighting a war across the whole expanse of France. From that day onward all dread possibilities and fears for disaster to our invasion were behind us. No longer was there any possibility of our getting kicked off. No longer would it be possible for fate, or weather, or enemy to wound us fatally; from that day onward the future could hold nothing for us but growing strength and eventual victory.

For five days and nights during that historic period I stayed at the front with our troops. The great attack began in the bright light of midday, not at the zero hour of a bleak and mysterious dawn as attacks are supposed to start in books. “The first planes of the mass onslaught came over a little before 10 A.M. They were the fighters and dive bombers. The main road, running crosswise in front of us, was their bomb line. They were to bomb only on the far side of that road. Our kickoff infantry had been pulled back a few hundred yards from the near side of the road. Everyone in the area had been given the strictest orders to be in foxholes, for high-level bombers can, and do quite excusably, make mistakes.

We were still in country so level and with hedgerows so tall there simply was no high spot – neither hill nor building – from which we could get a grandstand view of the bombing as we used to do in Sicily and Italy. So one place was as good as another unless we went right up and sat on the bomb line. Having been caught too close to these things before, I compromised and picked a farmyard about 800 yards back of the kickoff line. And before the next two hours had passed I would have given every penny, every desire, every hope I ever had, to have been just another 800 yards farther back.

Dive bombers hit it just right. We stood and watched them barrel nearly straight down out of the sky. They were bombing about half a mile ahead of where we stood. They came in groups, diving from every direction, perfectly timed, one right after another. Everywhere we looked separate groups of planes were on the way down, or on the way back up, or slanting over for a dive, or circling, circling, circling over our heads, waiting for their turn.

The air was full of sharp and distinct sounds of cracking bombs and the heavy rips of the planes’ machine guns and the splitting screams of diving wings. It was all fast and furious, yet distinct. And then a new sound gradually droned into our ears, a sound deep and all-encompassing with no notes in it – just a gigantic faraway surge of doomlike sound. It was the heavies. They came from directly behind us. At first they were the merest dots in the sky. We could see clots of them against the far heavens, too tiny to count individually. They came on with a terrible slowness. They came in “families” of about seventy planes each. Maybe those gigantic waves were two miles apart, maybe they were ten miles, I don’t know. But I do know they came in a constant procession and I thought it would never end. What the Germans must have thought is beyond comprehension.

They began like the crackle of popcorn and almost instantly swelled into a monstrous fury of noise that seemed surely to destroy all the world ahead of us. From then on for an hour and a half that had in it the agonies of centuries, the bombs came down. A wall of smoke and dust erected by them grew high in the sky. It filtered along the ground back through our orchards. It sifted around us and into our noses. The bright day grew slowly dark from it. By now everything was an indescribable caldron of sounds. Individual noises did not exist. The thundering of the motors in the sky and the roar of bombs ahead filled all the space for noise on earth. Our own heavy artillery was crashing all around us, yet we could hardly hear it.

It is possible to become so enthralled by some of the spectacles of war that a man is momentarily captivated away from his own danger. That’s what happened to our little group of soldiers as we stood watching the mighty bombing. But that benign state didn’t last long. As we watched, there crept into our consciousness a realization that the windrows of exploding bombs were easing back toward us, flight by flight, instead of gradually forward, as the plan called for. Then we were horrified by the suspicion that those machines, high in the sky and completely detached from us, were aiming their bombs at the smoke line on the ground – and a gentle breeze was drifting the smoke line back over us! An indescribable kind of panic came over us. We stood tensed in muscle and frozen in intellect, watching each flight approach and pass over, feeling trapped and completely helpless. And then all of an instant the universe became filled with a gigantic rattling as of huge ripe seeds in a mammoth dry gourd. I doubt that any of us had ever heard that sound before, but instinct told us what it was. It was bombs by the hundred, hurtling down through the air above us.

Many times I’ve heard bombs whistle or swish or rustle, but never before had I heard bombs rattle. I still don’t know the explanation of it. But it is an awful sound. We dived. Some got into a dugout. Others made foxholes and ditches and some got behind a garden wall – although which side would be “behind” was anybody’s guess. I was too late for the dugout. The nearest place was a wagon shed which formed one end of the stone house. The rattle was right down upon us. I remember hitting the ground flat, all spread out like the cartoons of people flattened by steam rollers, and then squirming like an eel to get under one of the heavy wagons in the shed.

An officer whom I didn’t know was wriggling beside me. We stopped at the same time, simultaneously feeling it was hopeless to move farther. The bombs were already crashing around us. We lay with our heads slightly up – like two snakes – staring at each other. I know it was in both our minds and in our eyes, asking each other what to do. Neither of us knew. We said nothing. We just lay sprawled, gaping at each other in a futile appeal, our faces about a foot apart, until it was over.

The bombing has decimated the target zone, but smoke had drifted towards the American lines and gathered horrific casualties. It was one of the worst friendly fire incidents in military history. The 30th Infantry Division total losses were 61 killed, 374 wounded, 60 missing, and 164 cases of PTSD (called combat fatigue at the time). An officer in the regiment remarked later that after the shelling his men, “stumbled ahead – as if walking in their sleep. Their hands and feet lacked coordination. They had the look of punch drunk fighters.” In their sector, Lieutenant General Lesley J. McNair was near a 120th Regimental command post to observe the bombings. He had been wounded before in North Africa by artillery shells visiting the front, but on July 25 a direct hit had thrown his body 60 feet from his foxhole and was completely unrecognizable except for the stars on his uniform. He was the highest ranking soldier killed in the European Theatre, a dear friend of Omar Bradley and fellow West Point graduate. The 4th suffered heavy losses with the 1st Battalion of the 8th Infantry Regiment. The 3rd Battalion of the the 9th’s 47th Regiment was badly mauled. Severe enough that they couldn’t muster an attack. They were replaced by 1st Battalion. Though the number fluctuated over time, in total VII Corps suffered 111 dead and 490 wounded.

Infantrymen scramble to dig out soldiers trapped in their foxholes after the bombing.

LAWRENCE TAKES THE GERMAN STRONGHOLD

On the far right flank of the bombing zone, the 9th Infantry Division was tasked with taking the town of Marigny and the high ground just south of it. The main road that connected Tribehou to Marigny would need to be secured, but reports from civilians said the road was heavily mined. The Division would have to secure all the fields around it, facing the Panzer Lehr Division that stood in its way. The responsibility of their objective was a heavy one as well. In order for Operation Cobra to succeed, the 9th would have to open the door all the way and keep it open against German counter-attacks. The 9th’s track record up to this point had been well established, the generals believed the 9th could do anything. However, General Eddy wasn’t so confident in his men anymore. They were tired and depleted. In the 10 days before Operation Cobra, they had received over 2,000 replacement soldiers. To keep winning the fights in the hedgerows, Eddy believed it was completely on the shoulders of disciplined, experienced leaders to take the initiative of small groups.

For the 2nd Battalion, their position was in the middle of the 9th, with 3rd Battalion on the right flank and 1st Battalion on the left near the 47th Regiment. The benefit of being on the far flank was their battalion was saved from the disastrous friendly fire that hit the 47th Regiment and could begin their advance on schedule. The downside was the German forces across their line had also been saved from the bombing.

The 2nd Battalion took off at 1100 hours and made their way to the St. Lo – Périers highway along with tanks from the 746th Tank Battalion. Their flanks had stalled, both the 47th and 330th Regiments failed to keep up with the distance the 60th had made. Col. Jesse L. Gibney had taken command of the 60th from Col. de Rohan at the beginning of the month and Major Max Wolf was commanding the 2nd Battalion after Major Kauffman was wounded the week before.

Top map shows the area in relation to St. Lo and Periers. Bottom map is courtesy of 9th Division historian and author Clement Derbaudrenghien. It shows the exact positions of the Division as they moved south to the St. Lo-Periers highway—now called the D900.

“First Lieutenant James Alford, a tank platoon leader in B Company, 746th Tank Battalion, was leading his five Shermans toward the St-Lo–Périers road. His Sherman was in the lead as his platoon crunched through a farmyard that was surrounded by stone buildings. “When we went around the farmhouse, there was a company of German infantry deploying in an open field.” Alford traversed his turret in the direction of the enemy and ordered his gunner to open fire. “[He] refused, saying I was mistaken and they were American infantry.” Lieutenant Alford could see the soldiers much better than his gunner. They had camouflage smocks and rounded helmets – the standard uniform of German paratroopers – so he repeated his order.

In the five seconds this exchange took, the Germans spotted Alford’s platoon. “I watched a German soldier fall prone upon the ground and aim his rifle at me.” Only the top of Alford’s head was above the turret, far enough that he could see but without exposing most of his head. This gave him a false sense of security, almost detachment, as he watched the enemy rifleman. “I bet he’s going to try to shoot me,” Alford thought.

The German paratrooper took aim and fired. “The bullet struck the front of my helmet, and the only thing I can compare the feeling to is if someone hit you on the head with a 10-pound sledgehammer. I can’t tell you what laws of ballistics or physics were at work, but that bullet went through the steel helmet, then followed the contour of the inner helmet liner across the top of my head and went out the back of the helmet at my neck. “It knocked me into the turret. Then my gunner was willing to open fire.”

The Sherman’s main gun boomed and the coaxial machine gun opened up. Lieutenant Alford lay still for a few moments in the turret, trying to regain his senses. “I was stunned … but immediately felt my head expecting to find blood and brains. The bullet carved some skin from the top of my skull and burned up the stash of toilet paper I kept tucked in the webbing of the liner. I had a hell of a headache for a few days [but] I got off real light. Two of my tank commanders weren’t so lucky. They were also hit by snipers in that farm complex.”

––––––––––––––––––––––––––

The 9th Division Official After Action Report for July 25th:

The Regiment’s position was astride one of the main north and south roads which First Army intended to use for armored columns in the plan for a major offensive. The mission of the Regiment was to clear the area immediately southwest of the crossing of the Champs-de-Losque – Marigny and the Periers – Saint-Lô roads. Three objectives were assigned: Objective “A” covering Hill 55 and the high ground north to the Periers – Saint-Lô road: Objective “B” covering the network of unimproved roads northeast of the road junction at: and Objective “C” covering the high ground between Montreuil and La Butte. Prior to the attack all units were withdrawn 1200 yards from the Periers – Saint-Lô road. The air preparation lasting for one hour and forty minutes was followed by a ten minute artillery preparation.

The attack jumped off at 1100 on the 25th at a rate of advance scheduled to reach the Periers – Saint-Lô road at 1130 under the cover of the last 20 minutes of air preparation and artillery preparation. The 3rd Battalion was on the right with its mission the capture of Objective “A”. The 2nd Battalion was on the left with its mission the objective of capturing “C”. The 1st Battalion followed the 2nd Battalion with the mission of passing between 2nd and 3rd Battalions and capturing objective B. During the withdrawal enemy groups had followed and during the advance to the Periers – Saint-Lô road some enemy resistance was encountered particularly on the right flank which was beyond the saturation zone of the air bombardment.

The 2nd Battalion moving down the main road received fire from its left as it passed the orchard. To avoid this fire it moved southwest across the field to Le Mesnil-Eury. Its advance developed only minor opposition and it was able to reach its objective at 1500.

The 3rd Battalion fought its way to the main road and turned west. Dealing with heavy enemy resistance, by night fall it was able to reach the northeastern part of its objective. The 1st Battalion following the 2nd Battalion met strong resistance in the vicinity of the road junction. In order to outflank this position, Major Sprindis personally led “A” Company south to Montreuil and then east to the road junction. During the night the remainder of the 1st Battalion was moved to this position.

––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Interview with Captain J. H. Withmore, Ass’t S3, 60th Inf. Rgt. And Lt.Col. Charles T. Fort, Ex. Officer of the Regiment:

25 July

0840 : 3rd and 2nd Bn began 1200 yards withdrawal again. This time they left a screening force of BARs and MGs, which did not withdraw until 0920. This was to prevent the German infiltration of our positions.

0920: A light barrage of 10 minutes was laid down to confuse the enemy into thinking that this was the prelude to attack, whereupon he would immediately get out and be vulnerable to the coming air attack.

0930: 350 light bombers worked south of the Periers road along the corps front until 1015 or 1030. Until 1200, the heavy bomber dropped loads on the area farther south. Heavies, however, did not bomb all the target, it seemed to Whitmore. The smoke bombs laid down as bombing line drifted to the north, as there was a south wind. The bombing therefore did not penetrate deep into enemy territory. One stick lit 800 yards to rear near 60th Field Artillery Bn and 16 E. One went to left 500 yards.

1200: Artillery reopened with 10 minutes preparation. At the same time, troops began to move forward from withdrawn position.

3rd Bn: By 1500 had reached objective (target A), and by 1900 had consolidated position on northern part of ridge. Since bomb objective did not include this area, the 3rd Bn encountered heavy resistance.

2nd Bn: Moved off at 1200 and reached objective C, about 1900.

1st Bn: Crossed Periers road mid-afternoon, followed through Le Mesnil-Eury. A Company in front, followed by B and C to an area north of Lozon.

––––––––––––––––––––

Operation Cobra, Notes, 25-29 July 1944:

At 1100 the 2nd Bn began its push forward from the area in which it had assembled during the bombing. It passed through elements of the 3rd Bn, and as it approached the village of La Couperie, it came under the fire of the enemy.

Although there had been selected points for attack by medium bombers on the north of the Periers – Saint-Lô road, the enemy resistance had not been seriously impaired in two areas. On the right of the divisional zone of action, in an orchard just north of La Mieterie. It was held by paratroopers, and since tanks and supplies could approach the orchard from the south, it was an excellent position. Enemy observation from one of the buildings in the orchard could call down artillery fire upon the American troops to the north. At one time, G Company of the 47th Infantry had held the woods, but before the 24th of July, it had been forced to withdraw. The field of fire across the flat meadows to the north of the orchard was excellent.

The enemy was likewise entrenched in the woods on the left of the regimental zone of action, just south of La Couperie. The thick underbrush as well as the heavy woods afforded excellent concealment. The enemy was well dug in, having covered foxholes. From the edge of the woods, he had good fields of fire. He used automatic weapons extensively and had bazookas as antitank weapons. This position was one of the most highly organized that the regiment had ever encountered.

After two hours and a half of slow progress against small arms fire, elements of the 2nd Battalion had pressed east of the strongly held wooded area on the right of its zone of action but had not yet succeeded in reaching the originally planned line of departure: the Periers – Saint-Lô road. With one company north of the wooded area, another to the east, the battalion was pinned down by fire throughout the afternoon. An element of the 4th Infantry Division moved in between 1800 and 1900 to relieve the company facing the orchard, thus releasing a further force to attack the resistance on the right. At 1920 the battalion pushed south, leaving one company to hold the enemy from the north. It then flanked the resistance, attacking from the southeast. The enemy was not cleaned out, however, by the time the battalion halted for the night.

Distinguished Service Cross

The President of the United States of America takes pride in presenting the Distinguished Service Cross (Posthumously) to Staff Sergeant Lawrence W. Gunderson, United States Army, for extraordinary heroism in connection with military operations against an armed enemy while serving with Company F, 60th Infantry Regiment, 9th Infantry Division, in action against enemy forces on 25 July 1944, in France. Staff Sergeant Gunderson's company was pinned down by heavy enemy fire from machine guns and an anti-tank gun. With complete disregard for his personal safety, Staff Sergeant Gunderson, armed only with a rifle and several grenades, skillfully maneuvered within close range of the machine gun and, exposing himself to observed fire from the gun, single-handedly wiped out the entire crew with grenades. Fearless and aggressive, he then attacked the crew of the anti-tank gun at point blank range. Though subject to direct small arms fire and receiving wounds in this encounter that proved fatal, his attack was so fierce that all members of the German anti-tank gun crew were killed or wounded. As a result of his action, the company was enabled to continue its advance. The extraordinary heroism and dauntless courage displayed by Staff Sergeant Gunderson in single-handedly destroying an enemy machine gun nest and an anti-tank gun crew set an inspiring example to his entire company. His intrepid actions, personal bravery and zealous devotion to duty at the cost of his life, exemplify the highest traditions of the military forces of the United States and reflect great credit upon himself, the 9th Infantry Division, and the United States Army.

A 1950 aerial map courtesy of Clement Derbaudrenghien shows the exact area where Lawrence charged the German’s position and how the area looked at the time with various tree orchards surrounding the woods. The small sporadic white circles are remaining craters from Operation Cobra’s bombings.

A present day image of the woods and orchards.

9th Division infantrymen push forward through the hedgerows in late July.

THE 9TH PRESSES ON

After Lawrence’s death on July 25th, the 9th Infantry moved on Marigny. They were the first outfit on the entire Cobra line to completely cross the St. Lo - Périers highway. Behind them, the 1st Infantry and 3rd Armored Divisions broke through, making Operation Cobra a complete success, minus the catastrophic beginning. The 9th had done more than just penetrate the German lines, taking the high ground to the west allowed an even larger door in which VII Corps could flow through. The 9th was held at Marigny to rest and receive badly needed replacement soldiers. By August 1st, they were back in business, engaged in the great “rat race” across the open fields of France. By mid-August they were attacking the Germans at the Falaise Gap. On August 19th, the division was forever changed when General Eddy was promoted to command the XII Corps of the Third Army. It was the end of two and half years of leading one of the most successful and influential divisions in the European Theatre. The 9th now moved by truck, instead of foot and passed by the southern villages outside the newly liberated city of Paris. By September 1st, they were at the French-Belgium border, and when they crossed it at 7:30 that evening, they were the first infantry division into Belgium.

September and October would bring much more casualties for the 60th Infantry Regiment. In September fighting through Belgium and into Germany, the regiment would suffer 1,200 dead, wounded, and missing – over half of their effective strength. By the end of October, its involvement in the horrific fighting in the Huertgen Forest would result in 100% turnover in combat personnel in the two month period. By Christmas of 1944, they were on the northern lines during the Battle of the Bulge. They crossed the Meuse River and in March they crossed the Remagen Bridge over the Roer River and into Germany. They pounded through the Nazi country in the spring of 1945 at places like Kassel, the Harz Mountains, Nordhausen, and into Wittenberg – where they shook hands with the Russians soldiers coming from the East. The war in Europe was over.